Were you driving through western Pennsylvania in the mid-nineteen-nineties, with the radio on? Was the music interrupted by two adolescent male voices jabbering trucker lingo? Or, several years ago, did you come across an online tourism video for the city of Milwaukee? Did it seem a little strange, in that the city shown was very obviously Manhattan, and that the video suggested that the entire Milwaukee area had been contaminated by an industrial accident? Or, sometime during the past few years, did you notice an account on Twitter called Horse_ebooks that spewed peculiar, mantralike messages such as “You’re not alone in your passion for tomatoes!” and “Demand Furniture”? Around the same time, did you happen upon a YouTube channel called Pronunciation Book, which consisted of videos of words in black lettering on a white background, and a calm male voice pronouncing each word three times, with great deliberation?

Jacob Bakkila and Thomas Bender—the pair behind these projects—were recently reminiscing about another collaboration, a play they wrote called “Cowboy,” which had nothing to do with cowboys. This was when they were in high school, in suburban Pittsburgh. Bakkila and Bender are now both thirty, but it’s easy to picture them as mischief-making teen-agers. Bakkila is a creative director at BuzzFeed, where he designs sponsored posts for companies like Pepsi and Geico. He is tall, with bristly blond hair, a square jaw, a sturdy neck, and biceps that look gym-made. He has a slight drawl that somehow sounds vaguely Texan. Bender works as a freelance tech consultant. He is slim and fair, clean-cut, with fine features, and speaks in a professorial tone. “We printed programs that made ‘Cowboy’ seem that it would be something like Gilbert and Sullivan meets Annie Oakley, which it definitely was not,” Bakkila said. He and Bender managed to lure a crowd to their high-school auditorium for the performance of the play, which was, in fact, an absurdist affair with an epic moment in which the actors stacked desk chairs until they came crashing down. Reaction to “Cowboy” was highly polarized: half the people couldn’t leave the auditorium fast enough; the other half seemed to think that the play was amazing.

A fifty-per-cent approval rating may sound disappointing, but Bender and Bakkila are less interested in winning approval than in eliciting a strong reaction, and by that measure their achievement has grown exponentially. According to YouTube’s analytics, the Pronunciation Book videos were viewed thirty-seven million times. Horse_ebooks’ most popular tweet, “Everything happens so much,” was re-tweeted more than nine thousand times by some of the account’s two hundred thousand followers. Bakkila and Bender operated both accounts anonymously, and trying to figure out who and what were behind them became an Internet obsession. On the day last September when they stepped forward to claim authorship, end the accounts, and launch an interactive video piece that they had designed as the final installment of the project, Pronunciation Book’s entry—“How to pronounce Horse_ebooks”—was one of the most viewed videos on YouTube.

Like the reaction to “Cowboy,” response to this news was divided, especially with regard to Horse_ebooks. Some people had thought that the account was an automated program that produced its utterances unwittingly, so when they learned that a person operated it, they were furious. Some saw it as a hybrid of a kind that the Internet is particularly good at enabling—a prank spread with the crazy multiplying speed of social media. Others simply couldn’t see what the fuss was about. Still others appreciated the project’s creative ambition. Christiane Paul, a curator of new-media arts at the Whitney Museum, said that its “play with identity, and the fusion of the human and the machine” placed Bakkila and Bender firmly within the genre known as “net art.” A Web developer named Aaron Grando and two of his friends started designing and selling Horse_ebooks T-shirts in 2012. They expected to sell a few dozen, featuring some of their favorite tweets, such as “Get ready to Fly helicopters.” Instead, they got orders from all over the world, and had to suspend the business because they couldn’t keep up with demand. “I think what they did was art to the most modern degree,” Grando said recently. He paused, and then added, “It was such a long con.”

—

Bakkila and Bender became best friends in the third grade and almost immediately began cooking up plans. “We published a newspaper when we were about eight years old,” Bender said. “Then we modified a CB radio so we could transmit to cars without anyone realizing where the sound was coming from.” In middle school, they drew comic books together and made claymation films; in high school, they took turns writing chapters of a serial novel, and dabbled in online radio. Then came “Cowboy.”

Bakkila went on to study journalism at the University of Southern California. Bender majored in physics at Princeton. In 2006, he saw “Vernon, Florida,” Errol Morris’s documentary about the eccentric residents of a small town. “I almost fell out of my chair,” he said. “I immediately started neglecting my classes to spend time making videos.” When he read a news story about a school for Wiccans in Illinois, he figured that he’d found a subject for his own documentary. By then, Bender had graduated, and had a temporary gig teaching physics at a cram school in Queens. He called Bakkila, who had also graduated, and was working at a coffee shop in Ithaca, and asked him to help. “Tom saved me from months of scalding myself,” Bakkila said. “I wasn’t a very good barista.” They drove to Illinois, shot the documentary, and Bender spent a year editing it.

The film, entitled “Hoopeston,” was released in 2008; it played in several small festivals and was received well enough that Bakkila and Bender decided to make another documentary. This time, they wanted to use the form to describe a fictitious world, and distribute it as if it were real, so that part of the experience would be the surprise of discovering it. Bakkila and Bender are aficionados of corporate babble and the unintentional humor of bad advertising; in the course of ordinary conversation, they often quote commercials and sales pitches. They thought that tourism-promotion videos, with their unalloyed cheerfulness and obfuscation of inconvenient truths, were wonderful in an awful way, and therefore perfect for re-purposing. They chose Milwaukee as their subject because they liked the name, and because neither of them had ever been there, which they considered a plus. At first glance, the ten-minute video, “This Is My Milwaukee,” looks like a typical bit of booster-ism, except for the perplexing glimpses of New York City landmarks. Then, about halfway through, the spokesperson—who speaks with a plummy English accent—mentions an “accident” at a local corporation called Blackstar. But, he adds merrily, “decontamination is well under way!”

Bakkila and Bender posted the video, listing themselves in the credits, on YouTube in November, 2008. Within three days, more than a hundred thousand people had viewed it. Some of them contacted local authorities to find out what was going on. “What the heck is ‘This Is My Milwaukee’?” a Wisconsin news site asked. “We’re getting deluged with e-mails asking us about a peculiar new Web site that just popped up.” Most people, though, seemed to get the joke. Five years later, Bender and Bakkila still hear from fans who want them to continue the story.

—

I spend a lot of time on Twitter, and I came across Horse_ebooks by chance, in 2012. I started following the account and re-tweeted it frequently. I wasn’t as passionate as those followers who tweeted “I love you” to the account nearly every day, but it was one of my favorite things on Twitter. I wasn’t sure what sort of sensibility was behind statements like “Who else wants to become a golf ball,” but I assumed that it was machine-made, since it sounded both brash and illogical, like a self-help book that had been run through a shredder. That October, I received an e-mail from someone whose name I didn’t recognize, asking if I wanted to know more about the account and, perhaps, write about it. Potential subjects don’t usually promote themselves to me in such a way, but I was interested in how that corner of the Internet works. To “satisfy the burden of proof” that he was in control of the account, the writer told me what he would post that evening. I watched Twitter, and saw the post.

I met Jacob Bakkila a few weeks later. In the middle of the conversation, he said that it was time for him to tweet—that is, time for Horse_ebooks to tweet. He logged in on his laptop and typed, “Are you ready to have a swan?” He hit return, and we watched the screen. Within a few minutes, more than a thousand people had re-tweeted the phrase, and hundreds had flagged it as a “favorite.”

There are lots of offbeat accounts on Twitter. Some feature invented characters, like “Ruth Bourdain,” a mashup of Ruth Reichl and Anthony Bourdain; there are parodies of politicians and celebrities, such as Anthony Weiner and Tilda Swinton; and pure surrealist humor, like that of coffee_dad, who has more than a hundred thousand followers and posts nothing but updates on his daily coffee-drinking. (“Time for coffee”; “Looking for coffee”; “Have coffee.”) There are automated accounts that are designed purely as curious exercises, such as Pentametron, which scans Twitter for posts that happen to be written in iambic pentameter, and Stealth Mountain, which collects tweets that misspell the phrase “sneak peek” as “sneak peak.” Then there is the category of “weird Twitter,” which essentially plays with the form. (In the early days of Twitter, Bakkila ran one such account, called agentlebrees; that name has since been taken over by someone else.) Horse_ebooks fits into the weird-Twitter world, but Bakkila prefers to describe it as “conceptual/performance/video art,” or, sometimes, as “performance mischief.” He says that the first art that enthralled him was Christopher Wool’s block-letter canvases of phrases like “CATS IN BAG BAGS IN RIVER.” Bakkila has a vivid memory of seeing one of Wool’s paintings at a museum when he was eight or nine. He told me, in an e-mail, “It amazed me how something so simple—it was just words!—could fill the room, fill my entire mind.” Many of the other artists who he says have influenced him, such as Jenny Holzer, also use text as their medium.

Making art on platforms like Twitter and Facebook, or by e-mail or in chat rooms, began almost as soon as those platforms existed. Net art’s most immediate predecessor was the Fluxus performance-art happenings of the nineteen-sixties, but its roots go back to the Dadaism of the early twentieth century. Vuk Ćosić, a pioneer of conceptual Internet-based art, has called net artists “Marcel Duchamp’s ideal children.” Like Duchamp’s readymades, a lot of net art defies the attributes usually associated with art: it isn’t singular, it doesn’t require the artist’s hand, it isn’t necessarily visual, it is often intangible, and, because it is usually distributed free, it is hard to collect and monetize.

Art has never been easy to define, and net art is even harder, since it frequently takes an existing form and simply alters it or interacts with it. Ben Grosser’s “Facebook Demetricator,” a widely discussed net-art piece, is a free plug-in that strips all numerical values off a Facebook page. In Joseph DeLappe’s “Quake/Friends.1,” another significant piece, six participants join a violent online multiplayer game, Quake III Arena, and reënact an episode of “Friends” while, in the world of the game, they are repeatedly killed. Aaron Betsky, the director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, who was the curator of architecture, design, and digital projects at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art from 1995 to 2001, told me, “This is the world young artists and art students live in. The way we represent our world is more and more digitally based and networked. If art is in any way reflecting our world, it will have to adopt and adapt these techniques and technologies.”

There isn’t a traditional market for net art, although a number of museums, including SFMOMA and the Guggenheim, have begun collecting it, and several Web sites, such as Rhizome.org, now run out of the New Museum, and netartnet.net, archive it. Rhizome’s collection, which was established in 1999, includes more than two thousand works, among them software, games, browsers, computer code, apps, and Web sites. In a way, net artists, existing outside mainstream art institutions, have a lot in common with early graffiti artists. The difference is that technology—and, in particular, social media—has made it simple for net artists to make their work accessible to millions of people almost instantaneously. Even so, being a net artist is rarely gainful. I asked Christiane Paul if anyone could support himself by working in the genre. “Well,” she answered, “I doubt a net artist could make a living right now making art.”

—

A producer was interested in developing a “This Is My Milwaukee” television series, but, after a year of talks, the plan fizzled. In the meantime, Bakkila moved to New York, and worked at various temp jobs, before ending up at BuzzFeed. Bender got a job as an editor at Howcast, a Web site of instructional videos. His first video, “How Not to Get Mugged,” starred Seena Jon, a middle-school friend of his and Bakkila’s, as the victim and Bakkila as the mugger. Bakkila, who occasionally freelanced at Howcast, helped write the script, which is more or less credible as a guide to street safety but also seems suspiciously like a goof on the whole idea of a how-to video.

Bakkila and Bender started thinking about a series of new projects. Jon, a former comedian who now works as a lawyer and a producer, became part of the team. They considered and then rejected the idea of telling a story through fake takeout menus slipped under apartment doors; forming a seemingly real trade association and issuing a monthly newsletter; opening a storefront to market a fictional clothing line; and aggressively promoting a new sports league that didn’t exist. One of Jon’s suggestions was to deliver a narrative through fortunes in fortune cookies, which would have been convenient, since Bakkila lived across the street from a fortune-cookie factory in Bushwick.

Bender was interested in “content farms”—Web sites that analyze which subjects are most frequently Googled, and then churn out material on those subjects so as to end up at the top of search results. The content is often just text grabbed from other Web sites and repackaged; the goal is to attract as many viewers as possible and then flood them with related advertising. Bender wanted to take the idea of demand-driven content to an extreme—to get as many views as possible while spending as little money as possible, as a kind of commentary on a form that tries relentlessly to convert a search for information into a chance for sales.

He knew that people Googled words and names in order to learn how to pronounce them. Making a pronunciation guide would cost next to nothing: he could find the words most often searched by typing in “how do you pronounce” and noting the words that Google offered. It was easy enough to produce type on a screen, and he recorded the pronunciations himself. He offered a new word each day; the first, posted in April, 2010, was “How to pronounce ASUS.” Bender says that he researched the way to say the words correctly. “It was initially very sincere,” he said. The videos immediately drew viewers who wanted to know how to pronounce the words he chose, and then, within a year or so, the channel drew another set of viewers, who were curious about its origins, its portentous tone, and its random-seeming choices, such as “Tagalog,” followed by “Srixon,” and then “giclée.” One of the videos—“How to pronounce 1999”—attracted more than three hundred and fifty thousand views. “It was really surreal watching the views grow,” Bender said.

—

Bakkila also found a medium that he thought he could hijack. Automated programs, known as bots, that deliver spam and sales links had been proliferating on social media. Last year, Bloomberg Businessweek reported that bots generate twenty-four per cent of all posts on Twitter. By Facebook’s own account, some fifteen million of its “users” are bots, which post sales links as status updates. Some bots are welcome—on Twitter, there are weather and seismic-condition bots, run by legitimate agencies, that post temperature and earthquake information. But most bots are the equivalent of junk mail, broadcasting e-commerce links in bulk, and both Twitter and Facebook devote considerable resources and manpower to flushing them out. To evade detection, bots masquerade as real accounts, so, in addition to the links, programmers give them something to say, or at least to appear to say—often snippets of text taken off the Internet—to make them seem as human as possible.

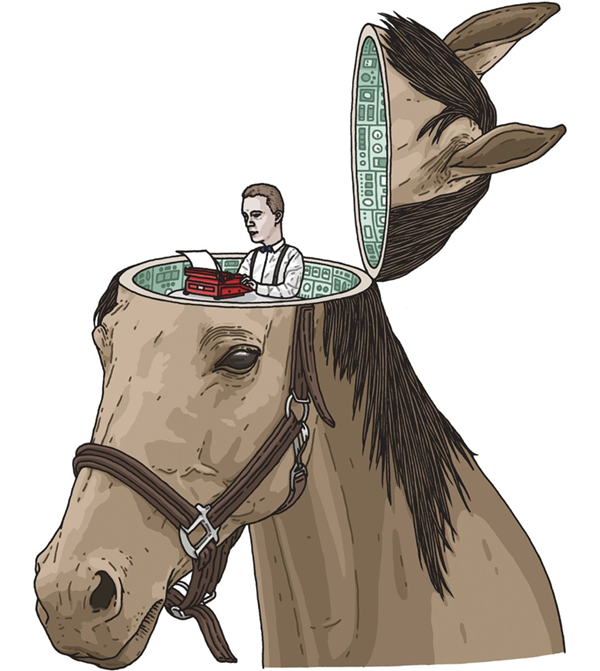

Bakkila decided to take over an existing bot on Twitter, and then slowly subvert its tweets. He wanted to attempt an identity inversion: he would be a human trying to impersonate a machine that was trying to impersonate a human. There were plenty of bots to choose from, but the one he liked best was Horse_ebooks, which appeared on Twitter in 2009. Its tweets often had an equine theme, but some, like “Considered GIVING UP on the whole professional gambling scene?,” seemed to come out of the blue.

Many of Horse_ebooks’ tweets were followed by links to e-library.net. The site sells e-books, some of which are about horses, but its most popular categories are inspirational guides and financial-advice books. It lists as its current best-sellers “Forbidden Psychological Tactics,” “Sexual Fun and Games for Christian Couples,” and “How to Buy and Sell Real Estate in the Bahamas.” The bot grabbed most of the text for its tweets from books on e-library.net, but, probably owing to a programming glitch, it often failed to pull out complete sentences, and it didn’t seem to be able to process certain punctuation marks. Many of the resultant tweets were half-formed, vaguely melancholy exclamations, such as “For many years this beautiful story has delighted millions of.” They were more peculiar and more evocative than bots usually are; they were like found poetry in an otherwise crass medium. By the time Bakkila came to Horse_ebooks, it already had hundreds of followers who loved its fractured tone.

In order to take over the account, he had to find the person behind it. You can set up a Twitter profile with nothing more than an e-mail address, but Bakkila followed links to e-library.net, and after six months he managed to track down a young Russian Web developer named Alexey Kouznetsov, who acknowledged that he owned e-library.net, and had set up Horse_ebooks to drive traffic to it. They agreed that, if Bakkila would buy two hundred and fifty dollars’ worth of books from e-library.net, Kouznetsov would give him control of the Horse_ebooks account. Kouznetsov remains the owner of e-library.net, and he told me that he sold between five and ten e-books a month through the account after Bakkila took it over.

Bakkila never wrote anything original for Horse_ebooks; like a bot, he just combed the Internet for text. (He had pulled the phrase that I watched him tweet at our first meeting from “The Essential Beginner’s Guide to Raising Swans.”) That part, he said, was easy: “There are so many weird, unindexed sites out there. When you go down the rabbit hole of spam, it’s an infinity of infinity.” He added, “One person could curate or remix endless amounts of information.” The first pulled text that he chose to tweet was “You will undoubtedly look back on this moment with shock and,” on September 14, 2011.

Bakkila was so excited by the prospect of playing a machine that he overlooked some of the challenges. Machines never sleep; bots post day and night and on weekends and holidays as well. He could have made a lot of tweets and programmed them to be time-released, but he decided to post in real time, because, as he put it, “I wanted to preserve the integrity of bespoke spam.” Bender, by contrast, recorded dozens of Pronunciation Book videos, then uploaded one each day, at his convenience. “Jacob really gets into these endurance things,” Seena Jon told me. “He likes to see how hard he can push himself.” Because Bakkila wanted to remain anonymous, he says that he didn’t explain even to close friends why he was excusing himself during dinners and movies.

Bakkila doesn’t remember the original context of his most popular tweet, “Everything happens so much,” but he says that it was something ordinary, like “Everything happens so much faster when you’re retired.” Stripped out of the sentence, the phrase feels koanlike. “I was trying to wrest wisdom from these wisdomless piles of information,” Bakkila said. A recurring theme in net art is appropriating something familiar and setting it in a new framework that makes it surprising. It’s especially surprising if you think that a machine is doing the decontextualizing unintentionally, and ending up with something that seems poignant or meaningful.

—

Shortly after Bakkila took over Horse_ebooks, some followers mentioned that the percentage of notably odd tweets seemed to be growing. As John Herrman, who is now the tech editor at BuzzFeed, wrote on the comedy Web site Splitsider, “The kinds of tweets that used to take weeks to show up—the perfect truncations, the ominous declarations—were now coming fast and hard.” After that, Bakkila, without revealing his involvement, persuaded an acquaintance to post a story dismissing the idea that the account had changed. (The acquaintance was extremely irritated when he later learned the truth.) He also worked to make the account look as botlike as possible, which is why he kept posting frequent links to e-library.net, as Kouznetsov had. “To be a sincere spambot, I wanted to try to sell as many e-books as possible,” he explained.

Horse_ebooks continued to attract attention. Adrian Chen wrote a long feature for Gawker about the “beloved online automaton,” which he described as being “showered with a level of praise seldom applied to actual humans on the Internet.” (Chen correctly identified Kouznetsov as the founder of Horse_ebooks, but he didn’t realize that the account had changed hands.) Fans started Tumblr accounts and Facebook pages, and created Horse_ebooks-inspired comics and fan fiction. At least one fan got a Horse_ebooks tattoo. An artist on Etsy produced letterpress stationery decorated with the tweets, and someone wrote a campaign speech composed entirely of them: “Every week it seems the economy” “Is uncertain, insubstantial” “Or going on a dangerous fad diet!” One guy posed as a woman and chatted on an online-dating site, using only the tweets, and posted the results on Tumblr.

—

Bakkila and Bender had planned that Pronunciation Book and Horse_ebooks would end with the launch of a third, very different sort of project, called Bear Stearns Bravo. It was meant to be a commentary on capitalism and the immorality of some corporate behavior. “Our formative years were in the Bush Administrations,” Bakkila said. “The financial crisis and the destruction of employment is all part of what we’re interested in. Businesses are characters, and corporations are people. And people are cells.”

Although Bear Stearns Bravo was to be launched last, planning for it began first. A few months after Bear Stearns collapsed, in March, 2008, Bakkila and Bender sat in Bender’s studio apartment, and began plotting a narrative that would be set in a fictitious version of the firm. They decided to use short live-action video segments and a format inspired by choose-your-own-adventure children’s books. The basic story would pit Bear Stearns employees against government regulators in a surreal financial emergency. After each segment, viewers would be given a choice: Arrest a suspicious secretary or get her to inform on executives? Butter up the C.E.O. or embarrass him in front of the board members? Meanwhile, employees burned documents and pined for more time on their yachts. (“In every project Tom and I have created,” Bakkila told me, “we have characters who regret owning boats.”) There were two episodes to the piece. They decided to make the first one available for free, but to charge users seven dollars for the second.

They worked on the project for four years, compiling hundreds of hours of videos. Seena Jon was the project’s producer, and Jamie Niemasik, a college friend of Bender’s who is now a software developer, wrote the program for navigating the videos. Only a few people knew the entirety of what they were doing; some people at BuzzFeed knew that Bakkila was working on videos but not what they were for. The actors hired for Bear Stearns Bravo were told only that they were taking part in something called “Untitled Video Project for Web Interactive Project.” One actor said, “All I knew was that I played an upper-management employee of an unnamed financial-services company. The character’s name was Billie, and she had anger-management issues.”

The videos were shot in a tiny, windowless room that Bakkila rented down the hall from his loft. On the day I visited, last summer, an actor, sweating amply, was shouting into the camera, “Multilevel marketing! Crystals! Stationary progressions!” Bakkila nodded, leaned over to Bender, and said, “Wow, that’s a wall of nonsense!” Next up was Bakkila’s girlfriend, Emily Liu, who was playing a small role that required her to deal a deck of tarot cards. Liu, who is an account executive at an online advertising agency, performed with an air of quiet bemusement. After the first take, Bakkila said, “Emily, I don’t want to direct your card dealing, but please put the last card down with . . . triumphalism.” After Liu managed to do a sufficiently triumphal take, Bakkila switched places with her. He hadn’t planned to be in the videos, but he ended up taking the role of the C.E.O., because he and Bender couldn’t find anyone they felt was right for the part, which was physically taxing—the C.E.O. bellows all his lines. By the end of the day, Bakkila had blown out his voice, but he seemed pleased with the results.

—

No one would have suspected that a slightly bizarre, faceless YouTube channel and an apparently automated Twitter account had any connection. If you paid close attention, you might have noticed a few common notes—mentions of the names Dalton and Chief, and frequent references to tomatoes and pyramids—but, otherwise, the sites appeared to be separate entities, each with its own mysteries. Online forums studied Pronunciation Book’s word choices and even the ambient background noise in each video; one generated a file of more than a hundred pages trying to decrypt the site. Once Bakkila and Bender settled on a launch date for Bear Stearns Bravo, Bender began posting full sentences on Pronunciation Book and then started a countdown—“Something is going to happen in seventy-seven days”—that sounded especially ominous.

“There were wild conspiracies,” Bender said. “One guess was that Edward Snowden was behind it. Another was that it was a Syrian operative.” Other people assumed that Pronunciation Book was a slowly unfolding promotion for a new smartphone or a Batman movie or a reboot of the “Battlestar Galactica” TV series—not bad guesses, since so many seemingly authentic Internet phenomena have turned out to be marketing campaigns: the narrative around a fake beekeeping site, ilovebees.com, for instance, was revealed to be a promotion for the video game Halo 2. But the cyberpunk novelist William Gibson tweeted, “The content of that YouTube channel smells of fiction. Those of us who slave in the factory know the smell.”

Last July, two months before Bear Stearns Bravo was set to launch, Bender, who doesn’t have a Twitter account and isn’t even on Facebook, realized that someone had posted his name and telephone number in connection with Pronunciation Book. He was barraged by calls, and then someone showed up at his office, announcing himself as “Chief.” Around the same time, Gaby Dunn, a reporter for the Internet news site the Daily Dot, figured out Bender’s association with Bakkila. When she contacted Bakkila, he scrambled for a cover story, ultimately telling her that he and Bender had been assembling a secret project that might have a movie component, and he needed time to line up more funding. She agreed to postpone her story. Bakkila now says that he wasn’t seeking any financial deal, and admits that he lied to Dunn to stall her. He said, “You get one chance to introduce yourself as an artist. This was it.”

Bakkila and Bender wanted to launch Bear Stearns Bravo with a performance, so they found a gallery on the Lower East Side that would rent them space for a day. They planned to post a phone number on Horse_ebooks at ten in the morning, and man the phones for the next eleven hours. They would read a line of spam to each caller and then hang up. The gallery would be open to anyone who wanted to watch. Loops of video from Bear Stearns Bravo would be projected onto the walls.

The night before the launch, Bakkila, Bender, Jon, Niemasik, and Liu gathered in the gallery to set up the projectors and install the phones. Bakkila placed an artist’s statement near the front door that began, “We are influenced by data,” and went on to say, “Bakkila has . . . performed, in secret, as a spambot on the social network Twitter, posting a piece of spam roughly every two hours for 742 days.” (In total, there were eighteen thousand tweets, including Kouznetsov’s.) Bakkila said that he expected to feel a little depressed once he ended Horse_ebooks, the way an actor might feel at the end of a play’s run, but that he couldn’t spend the rest of his life performing as a machine.

In the morning, a few friends milled around; they had agreed to help with logistics but still didn’t know what the project was. One of them, reading the artist’s statement, started sputtering, “What? Jacob wrote all Horse_ebooks . . . a machine didn’t. . . . This is . . . . Wow.” Bakkila and Bender sat down at a conference table, each armed with a phone and a stack of printouts from which to read. I sat at a third phone to watch the proceedings and answer a few calls. At exactly ten o’clock, the Pronunciation Book video of the day demonstrated how to pronounce “Horse_ebooks,” and Horse_ebooks tweeted the gallery telephone number, followed by its last tweet, “Bear Stearns Bravo.” Within a minute, all three phones began ringing. A few times when I answered, I heard the caller laughing. One person yelled, “What does this have to do with Horse_ebooks? Tell me! Tell me!” The phone I was watching registered almost four hundred missed calls in the first twenty minutes. In addition, Bakkila and Bender claim that, by the end of the day, a hundred thousand people had visited bearstearnsbravo.com.

Shortly after word got out on social media, people began showing up at the gallery. One young man in an olive drab jacket leaned against the wall for most of the day, taking pictures of Bender and Bakkila and scribbling notes. He told me that he loved Horse_ebooks, and had never been sure if it was a human or a bot, or maybe, he said with a sidelong glance, some entirely new life form. “Nobody knew,” he said. “Nobody knew.” He took another picture and then said in a quiet voice, “This is something to tell my grandkids about someday.”

—

The team had expected people to be surprised—maybe even shocked—when they shed their online personas, and people were. “Horse_ebooks is over,” someone posted. “I can’t deal.” Obituaries were put up on Tumblr and Facebook. Adrian Chen, who had written first about Kouznetsov, remembers feeling “extremely unsettled—like I was waking from a dream.” Many people were angry not only because a favorite Twitter account was ending but also because they felt cheated that Horse_ebooks wasn’t what it had seemed; it wasn’t an unintentional oracle but the work of one person who plotted its course. Because Bakkila works for BuzzFeed, the company was suspected of having a hand in Horse_ebooks, which compromised the account even more in the eyes of some fans. But John Herrman, the site’s tech editor, said that “across the board, people at BuzzFeed were completely surprised.” (The editor-in-chief, Ben Smith, later told the editorial staff that he was willing to keep secrets, but preferred having advance notice of what staffers were up to in their free time.)

People complained bitterly about many things: that charging to play the second episode of Bear Stearns Bravo was a sellout; that it couldn’t have been physically possible for Bakkila to have posted around the clock; that he and Bender were more mercenaries than artists; that they were overeducated Brooklyn hipsters manipulating the public; and that, in the end, Bear Stearns Bravo was just a big bore. Others were more philosophical. “@Horse_ebooks was a fiction,” Robinson Meyer wrote in The Atlantic. “It was about the network and it took the form of network. It was loved by many users, a semi-daily treat in their feed, and hated by others. . . . It was the most successful piece of cyber-fiction of all time.” Chen told me that, after he got over the initial jolt, he saw it as “an amazing performance,” even though it spoiled the illusion that the Internet could spontaneously produce something pure and beautiful. “I’m happy it was a human,” he said. “In the end, humans win—even at being robots.”

Horse_ebooks and Pronunciation Book aren’t the first art projects to rile people and leave them feeling betrayed; net art often makes use of ambiguous identity and deliberate misdirection. By definition, it examines the nature of our relationship to machines, and the notion that machines or computer systems might be closer to sentience than we realize.

This isn’t only a contemporary preoccupation. Machines have always enraptured us because they are perfectible systems that can surpass human limitations. Several people, in discussing Horse_ebooks, have pointed to the work of Joseph Weizenbaum, a professor of computer science at M.I.T., who, in the nineteen-sixties, wrote one of the first artificial-intelligence bot programs, which he called Eliza, after George Bernard Shaw’s heroine. It could mimic the tone of a Rogerian therapist, by repeating phrases back to whoever was interacting with it. Weizenbaum was concerned by how involved in the program people got, and noted that his secretary would ask him to leave the room when she was “talking” to Eliza. In his 1976 book, “Computer Power and Human Reason,” Weizenbaum wrote, “Extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.”

At other times, we’ve mistaken a human for a machine. Some people commenting on Horse_ebooks have also mentioned an automaton called the Turk, which was introduced, to great acclaim, in Austria, in 1770. The metal-and-wood contraption, which was designed to look like a man and was dressed as a sorcerer, amazed audiences by playing master-level chess against human opponents around the world, for seventy years. The secret of the machine was that it wasn’t really a machine. The mechanical body had a concealed cabinet behind its gears and cogs, and a real chess master hid inside it and directed the Turk’s moves. In 1854, the Turk, which had been stored in a museum in Philadelphia, was destroyed in a fire. Many people still believed it was a robot that had acquired an uncanny, humanlike intelligence. Its last owner claimed that he heard the Turk calling out as it went up in flames.

Bakkila didn’t appear upset by the uproar, even when it seemed as if every social-media blog and Internet forum were raging at him. “I did want to create an uncomfortable situation,” he said. “I wanted a tension between the human and the artificial. I don’t fault anyone for an emotional response. It was designed to be emotional.” Recently, I asked him and Bender if they were on to their next collaboration yet. They avoided answering, but Bakkila finally said, “We’ve been doing stuff together most of our lives. I’m sure there will be more to do.”